Disability Matters Online Symposia June 2025 from Toronto, Canada

This is a free event held fully online via Zoom on Monday 2nd June, 2025.

This online symposium follows the conversations at the Disability Matters ∞ Ways of Perceiving Spring Institute at Toronto on 30th May and explores how disability matters and the ways that we perceive as critical to our lives together.

Read more about Disability Matters ∞ Ways of Perceiving.

A caption-only version of this recording is also available.

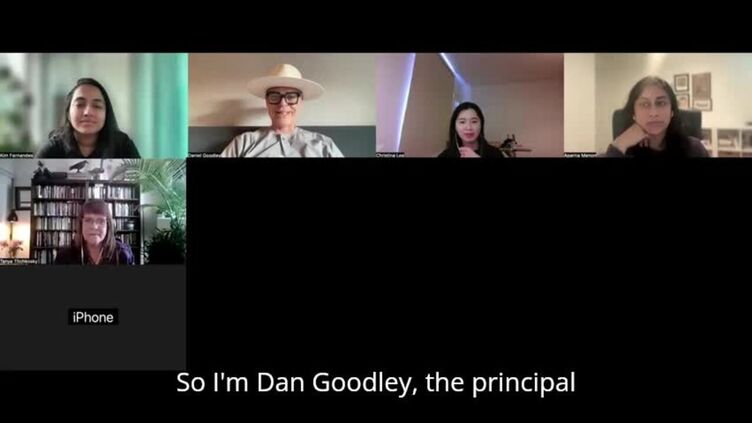

Chair: Dan Goodley

Facilitator: Christina Lee

Speakers

Aparna Raghu Menon (she/her)

Aparna Raghu Menon is a Ph.D. Candidate in Public Health Sciences at the University of Toronto. Her SSHRC-funded doctoral project draws on critical disability studies, communication studies, posthumanism and feminist frameworks to investigate the intersections of autism, health and communication amongst non-verbal autistic children and adolescents.

Title: Examining the frames of reliability and productivity in non-verbal autism: A critical disability studies approach

Abstract: In this paper, I explore whether the possibilities of autistic communication are fulfilled only by a successful completion of the communicative act or whether such possibilities exist simultaneously within the risks carried by failure-laden communication or a silent refusal to communicate. To do this, I draw on Titchkosky’s and Michalko’s ideas of how disability-framed-as-problem reproduces endless renderings of the problem of disability while leaving the frames completely unexamined (2017).

Kim Fernandes

Kim Fernandes is a researcher, writer and educator interested in disability, data and technology in urban India. They are currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Faculty of Information at the University of Toronto. Fernandes holds a joint Ph.D. with Distinction in Anthropology & Interdisciplinary Studies in Human Development in 2024. Their recent work has been funded by the Social Science Research Council and the Taraknath Das Foundation’s Marion Jemmott Fellowship. Fernandes also holds an M.S.Ed. from the University of Pennsylvania, an Ed.M. in International Education Policy from Harvard University, and a B.S.F.S. (honors) in International Politics from Georgetown University.

Title: Skepticism with/in/as Crip Technoscience: Disabilities and Technologies

Abstract: Where and how might we place skepticism in understanding what technology does to/for disability, and vice versa? This reflection attends to disability as cultural production through technology (assistive and otherwise) with the intention to locate both productive and difficult tensions in how we come to think of what technology is "good" for. Beginning with an attention to the assumptions that often shape the development of new technologies in the popular cultural imagination, this reflection will then move to a meditation on the role of skepticism within the praxis of crip technoscience. In asking how disabled people and communities respond to technoscientific advances, the reflection also attends to how and where (else) we might make meaning of narratives of progress.

iHuman

How we understand being ‘human’ differs between disciplines and has changed radically over time. We are living in an age marked by rapid growth in knowledge about the human body and brain, and new technologies with the potential to change them.