Special Collections and Archives

Special Collections is home to over 30,000 rare books, periodicals, and pamphlets printed before 1851, along with some later rarities. Our Archive collections, which number over 200, cover a broad range of subjects of academic interest, which have flourished over the years as new research interests.

About Special Collections and Archives

Our special collections and archives provide primary source material to support teaching and research for members of the University faculty-wide, as well as those from other national and international institutions, and independent researchers.

Our collections’ particular strengths are in Restoration drama, English Civil War tracts, travel and exploration from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, social and political caricatures from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists’ and private press books, and avant-garde poetry pamphlets from the 1950s to the present day.

Our archives are collections of the papers of individuals and organisations. Examples include the Hartlib Papers (correspondence to the seventeenth century polymath Samual Hartlib), the Jack Rosenthal Drama Scripts Collection, the Papers of Richard Hoggart, the British Union (of Fascists) Collection, and the Papers of Sir Hans Krebs, Nobel Prize-winning biochemist. Recent acquisitions include the papers of the British communist journalist Alan Winnington, the archives of politician David Blunkett, and the papers of the poet Peter Redgrove.

We hold specialised, usually subject-based, book collections such as the Holocaust Collection, the Left Book Club Collection, and the Elmfield Collection (glassmaking). Our book collections also include personal libraries, often including rare, unusual, or annotated volumes.

Highlights of our Special Collections:

- The Rare Books Collection

-

The Rare Books Collection consists mainly of volumes printed before 1851, but it also contains titles published after that date if they are rare or interesting in other ways such as signed or annotated. The collection covers many subject areas including history, language and literature, drama, mathematics and all the sciences, philosophy, religion, architecture, law, natural sciences, and travel and exploration. Several thousand volumes were presented by the Sheffield-born historian Sir Charles Harding Firth (1857-1936) soon after the opening of the University in 1905. Firth had been Lecturer in Modern History in Firth College before becoming Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford.

Among Firth’s donation is an extensive collection of English Civil War tracts, a collection of hundreds of 18th and 19th century caricatures by artists such as George Cruikshank and Thomas Rowlandson, which are in the process of being digitised, and a notable 17th century (Restoration) drama collection.

Contemporaneous to Firth, the Reverend John E. B. Mayor (1825-1910) donated over 200 rare books from his own library. Mayor was a classics scholar at Cambridge, a noted vegetarian and campaigner for a vegetarian lifestyle. His donation consists of mostly Latin and Greek texts, but does include other languages.

- The Private Presses Collection

-

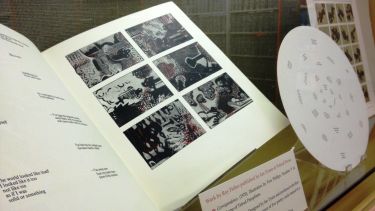

The origins of the Private Presses Collection lay in the 1960s with a generous donation, and a legacy. Sheffield-based artist and entrepreneur Annie Bindon Carter visited the newly-built Western Bank Library in 1962 and donated the sum of £1,000 (over £20,000 in today’s money) specifically for the purchase of artists’ books. She wanted students to be able to read outside of their areas of study to broaden their education, and be changed by art. Inspired by Carter, alumna Dorothy May Goodby bequeathed her estate to the University and declared that the artists’ books collection should benefit from the yearly interest of her investment, something that continues to this day.

The Private Presses Collection includes examples of key British independent fine presses founded by book artists such as Ron King (Circle Press), Ian Tyson (Tetrad Press, ed.it), Tom Phillips (Talfourd Press), and Ken Campbell. It also includes important works by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, Golden Cockerell Press, the Nonesuch Press, the Chiswick Press, Petersburg Press, Editions Electo, and many others.

- Special Political Collections

-

Over the years, our special collections have been developed and used for teaching and research at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The most well-established and numerous of these are the left- and right-wing politics collections which between them include several hundred books and pamphlets some of which are scarce copies. The book collections run in parallel with similarly themed archive collections.

- The Small Press Poetry Collection

-

This collection contains material unavailable in any other British institution. It focuses on British and American poetry and art of the avant-garde from the late 1950s onwards. We are also developing our British Poetry Revival pamphlets, and more recently published titles from young, independent presses. The collection is continually being added to in support of teaching and research with a focus on Black Mountain, the New York School, and the San Francisco Renaissance. Recent acquisitions include artist William Copley’s S.M.S. portfolio (1968), and former academic Gordon Brotherston’s papers and pamphlet collection, notable for its collection of Edward Dorn titles and modern poetry in translation.

Unique to the United Kingdom, the University of Sheffield Library holds complete collections of two significant Canadian small presses: Weed/Flower Press, founded and run by the prize-winning poet Nelson Ball; and Seripress, founded and run by the painter and poet (and wife of Nelson Ball), Barbara Caruso.

Here are some highlights of our Archive Collections:

- Madeleine Blaess Diaries

-

Madeleine Blaess was born in Alsace-Lorraine, France in 1918. As a child, she moved to York with her parents and then went to Leeds University to study French in 1936. She graduated with a First Class Honours degree in 1939, and in October 1939 secured a bursary for doctoral research at the University of Paris and at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes.

She was unable to return to Britain in 1940 due to the rapid German advance and so spent the war in occupied Paris. Madeleine kept a diary for the next 4 years as a replacement for sending letters to her parents. She recorded a day-by-day account of life under Occupation, as she continued to pursue her goal of becoming an academic under increasingly difficult physical conditions and psychological strain.

In October 1948, she was appointed lecturer in the Department of French at the University of Sheffield, where she remained until her retirement in 1983, having concentrated her research and teaching on mediaeval French. Madeleine Blaess died in 2003 and she bequeathed her books and papers to the University.

The diaries are kept in the University of Sheffield Special Collections and are written in French. They have been edited and translated by Dr Wendy Michallat, titled 320 rue St Jacques, The Diary of Madeleine Blaess, published by the White Rose University Press.

Read more about Madeleine Blaess

Madeleine's Diaries can be searched on our online archive catalogue:

- The Winnington Papers

-

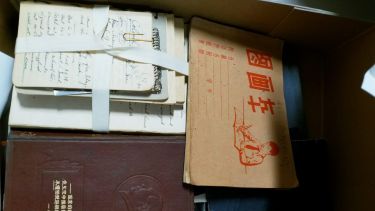

The archive of journalist Alan Winnington held by Special Collections at the University of Sheffield Library is a fascinating collection in its own right. It’s 47 or so archive boxes contain first hand accounts of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Korean War, as well as life in communist East Berlin, all documented within notebooks, articles, correspondence and photographs.

However, the material’s uniqueness truly becomes apparent when it is also understood that this collection - unlike contemporary material from other journalists - is delivered by a British eye-witness from a communist perspective. The Library is pleased to open the archive to researchers for the first time, providing an intriguing insight into one of the most fascinating periods of East Asian, European and Cold War history.

The Alan Winnington Papers can be searched on our online archive catalogue:

- The Blunkett Archives

-

The Blunkett Archives is a unique collection of national importance which records the former Home Secretary’s remarkable journey from a working-class community in Sheffield to the highest level of British politics. One of the most significant aspects of the collection is that it covers a transformative period in British political history from a unique perspective - that of the first blind cabinet minister in the UK.

Blunkett had an interest in politics from a young age. He joined the Labour Party at the age of 17, and was active in local politics in both Shrewsbury and on his return to Sheffield. He soon decided that he wanted to become more involved in the decision making processes and put his name forward to be a candidate for election to Sheffield City Council. He was selected to stand for his own ward of Southey Green, a traditionally safe seat for the Labour Party, and he was elected with a comfortable majority in May 1970. At the age of only 22, and still a student, Blunkett was the youngest ever member of the council. In 1973 he went on to take up a position of Lecturer in industrial relations and politics at Barnsley College of Technology and undertook the two roles side by side for a number of years. In 1980 he became the youngest ever Leader of Sheffield Council.

The Blunkett Archives can be searched on our online catalogue:

- Irene Champernowne Archive

-

Irene Champernowne was a leading psychotherapist in the UK, who pioneered the integrating power of creativeness to improve mental health and whose vision was to make psychotherapy available to all. Influenced by Carl Jung’s psychoanalytic theories, Champernowene pioneered art therapy as a source of treatment which is still used in today’s therapeutic practices.

Irene was born in London in 1901 and grew up in a religious household, and she kept a deep faith throughout her life. She studied at Birkbeck, University of London, however by 1925 the stress of her studies alongside working to financially support herself led to significant mental turmoil. She spent the year after graduation recovering on a farm with friends, but remained haunted by an early formative experience in her life. Her cousin had had a breakdown after returning from fighting in the First World War and was hospitalised for the rest of his life. As an adolescent she considered becoming "a mental doctor" as "this might redeem [her] cousin's endless pain". Whilst recovering from her depression at the farm she went for her first analysis, and this proved to be the first step in her career working to improve mental health.

The archive collection was recently donated to The University of Sheffield Special Collections and Archives by The Champernowne Trust and will be available to search online in the future.

'The Power of Creativeness: Champernowne, Withymead, Jung' is exhibited in Western Bank Library until 25th June 2023.

Search the Collections

Keep in touch:

- Advisory Committee

-

Anna Clements, Director of Library Services and University Librarian (Chair)

Angela Haighton, Associate Director (Cultural Collections and One University)

Bob Johnston, Professor of Landscape Archaeology

David Meadows, Senior Philanthropy Manager - Legacies

Marcus Nevitt, Senior Lecturer in Renaissance Literature

Greg Oldfield, Head of Public Engagement, Partnerships & Regional Engagement

Lauren Rea, Professor of Latin American Studies

Mariam Yamin, Senior Archivist Special Collections (Secretary)

Simon Stevens, Lecturer in International History

Helen Woolley, Professor of Landscape Architecture, Children's Environments and Society

Matthew Zawadzki, Head of Records Management & University Archive

- Policies

-

Discover Our Archives Accessibility Statement

Special Collections and Archives Care and Conservation Policy

Special Collections and Archives Collection Development Policy