National Fairground and Circus Archive

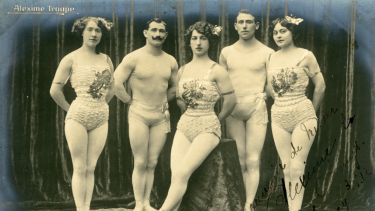

The National Fairground and Circus Archive (NFCA) embodies the history of popular entertainment from the seventeenth century onwards. It covers every aspect of travelling entertainment culture and contextualises its evolution, cross-cultural impact, and global spread and influence.

About the NFCA

The NFCA covers every aspect of the fair, circus and allied entertainments, and the culture, business and life of travelling show people under the unified identity of leisure history, the evolution of showmanship and travelling show people as a defined community.

We hold a vast collection of records on fairground, circus, variety and music hall, magic, sideshows, boxing booths, traveling cinematograph shows, pleasure and zoological gardens, amusement and theme parks, menageries, performing animals, optical illusion, traveling exhibitions, seaside entertainment and world’s fairs and expositions. Also in its collection can be found a large library containing books and journals covering all relevant and associated topics.

The Archive provides a primary source of research and teaching material across a range of subject disciplines from the unique viewpoint of the popular entertainment industry including: history, science and engineering, architecture, animal and human science, economics, business, law, philosophy, art and psychology.

Here are some highlights about the collection:

- Bill Barnes Collection

The Bill Barnes Collection is one of the most important collections of early British cinema ephemera in the UK. It was curated by leading film historian, author, and collector Bill Barnes (1920-2019). The Collection comprises programmes, photographs and other documents related to the Poole family, who travelled pre-cinema and moving picture shows around Britain for 100 years from 1837.

- Circus Friends Association Collection (CFA)

The CFA Collection is the largest public collection of circus history in the UK. It comprises a Library holding over 1,000 titles and an archive containing thousands of documents, posters, photographs, programmes and other items of ephemera, dating from the 1800s to today.

- John Bramwell Taylor Collection

The John Bramwell Taylor Collection was compiled by John Bramwell Taylor, an avid collector of popular entertainment ephemera. The collection comprises thousands of rare documents related to shows of London including the Egyptian Hall, The Polytechnic, Regent Street, The Royal Agricultural Hall, Bond and Oxford Street, Leicester Square and others.

- The Shufflebottom Collection

This collection is the archive of the Shufflebottom family who travelled wild west shows around the fairgrounds of the north of England for four generations. Originally from Yorkshire, the Shufflebottom family are a prime example of the influence of Buffalo Bill and the American wild west in Britain.

- Orton & Spooner Collection

Orton and Spooner were one of the most significant engineering companies to build fairground rides and equipment in Britain. They were responsible for producing some of the most sophisticated and sought-after wagons, rides and shows to travel the British fairs between 1875 and 1954.

- Barbara Buttrick Collection

Barbara Buttrick ‘The Mighty Atom of the Ring’ started her boxing career on the fairground booths with Professor Bosco and Sam McKeowen. In 1853 she went to America and joined an Athletic Show which travelled the Midways, a year later she started fighting competitive bouts and became one of the most famous women boxers of all time and the first female boxer to have her fight broadcast on national television.

Search the collection

Digital National Fairground and Circus Archive

Keep in touch:

- Our Advisory Committee:

Angela Haighton, Associate Director (Cultural Collections and One University) (Chair)

Professor Vanessa Toulmin, Director of City & Cultural Engagement, Partnerships and Regional Engagement and Chair of Early Film and Popular Entertainment, School of English, University of Sheffield

Graham Downie, Editor of the Fairground Mercury and Chairman of the Fairground Association of Great Britain

Desmond FitzGerald, Public Affairs Manager, The Showmen's Guild of Great BritainJohn Exton, Vice President of The Circus Friends Association of Great Britain and Council Member responsible for liaison and support with the National Fairground and Circus Archive

Dr. Stephen Walker, Lecturer, School of Architecture, University of Manchester

Advisory Emiritus: Anthony D. Harris, Former President of the Showmen's Guild of Great Britain

Professor Dawn Hadley, Professor of Medieval Archaeology, University of York

Kathryn McKee, Head of Special Collections, Heritage, and Archives

Steven McIndoe, Faculty Librarian for Arts and Humanities

- Our Policies: