We are feminists: Black feminism at the University of Sheffield - A beginner's guide

I’m indebted to black feminism. It’s the only debt I’ve had where I revel in the sense of owing and where my "repayment" is measured in terms of how lavish I am with my spending. The more I borrow, the less I owe, and the more I spend, the richer I become. This is my attempt to pay it forward.

If I hadn’t read black feminist works at key moments in my life, I probably wouldn’t have been bold enough or brave enough to pursue a career as an academic in what is a predominantly white and male research environment.

It wasn’t a coincidence that it was while reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple that I mustered the courage to apply to a very privileged group of universities when at that moment I was living in a council flat and working as a cleaner at a local private school.

It wasn’t a coincidence that it was after a presentation I gave on Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens several years later at The University of North Carolina, that classmates suggested I become a university lecturer.

I know for a fact that reading the preface to Patricia Hill Collins’ Black Feminist Thought on the bus on the way home from work prevented me from quitting my PhD. In the Preface to the First Edition, Collins reflects:

Beginning in my adolescence, I was increasingly the “first,” or “one of the few,” or the “only” African-American and/or woman and/or working-class person in my schools, communities and work settings. I saw nothing wrong with being who I was, but apparently many others did.

My world grew larger, but I felt I was growing smaller. I tried to disappear into myself in order to deflect the painful, daily assaults designed to teach me that being an African American, working-class woman made me lesser than those who were not. And as I felt smaller, I became quieter and eventually was virtually silenced.

(Collins, ‘Preface to First Edition’, p.vii).

Like Collins, I found (and find myself) repeatedly “among the few” women of colour in higher education, but when I read the passage above I realised that quitting my PhD would be tantamount to accepting my voicelessness and so I continued, I continue and I’m still here. And although there are times when I feel as though I’m disappearing, when I waver, I return to her words for sustenance.

You see, black feminism is more than just a theory or paradigm. It offers me the tools I need to be effective in my professional and personal life. Walker defines a womanist or “feminist of colour” as one who engages in, “outrageous, audacious, courageous or wilful behaviour”, who is “wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered ‘good’ for one”.

When I applied to University, then studied abroad, achieving top marks all the way and then against all sensible advice worked three part-time jobs to support myself through a PhD, I was, I am and I continue to be outrageous, audacious, courageous and wilful – defying people’s expectations of me. And I flagrantly and unapologetically share and celebrate black feminist thought in my teaching and research in the hope that others feel inspired to do the same.

So it’s obvious why black feminism matters to me. But what does black feminism mean to you? If you’re not a black woman or if you don’t study black women’s writing or history, is black feminism even remotely relevant?

The short answer is if you support our University’s commitment to equality and diversity, widening participation, internationalisation and civic engagement, then yes, it is relevant.

Black feminism offers us a set of tools with which we can dismantle, challenge and confront the sometimes blatant but often insidious ways that racism, sexism, colonialism, imperialism, xenophobia, and capitalism collude to exclude women of colour from the places and spaces where power resides.

We can use black feminism to break down those restrictive and false binary oppositions between men and women, black and white, east and west, rich and poor to create a more inclusive society. And so it doesn’t matter whether you’re from Croydon or China, wherever you are, whoever you are, to borrow from bell hooks (another feminist of colour I adore), Feminism is for Everybody.

Black feminism can help support our ambitions to achieve and sustain a more diverse student and staff body, not just symbolically in our research and on our reading lists, but literally in our classrooms, in our boardrooms, as heads of departments, chairing groups, as our lecturers, as our leaders, making We Are Feminist videos pushing forward our shared agendas and goals as a University community.

Black feminism is pertinent in the way it stretches out far beyond the classroom too, shedding light on spaces and people outside of the academy and other arenas of privilege to help us arrive at a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of why women matter.

Alice Walker offers us the image of her mother working in her garden to help us understand the completely underrated role black women play in creating and nurturing the genius that we as academics feel it is our duty (pfft) to gate-keep. “Her face”, Walker writes about her mother, “as she prepares the Art that is her gift, is a legacy of respect she leaves to me, for all that illuminates and cherishes life”. “She has handed down respect for the possibilities – and the will to grasp them” (‘In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens’, pp. 241-242).

No image is more poignant to me than that of Walker’s mother, (or indeed my own) tending to her flowers and plants, nurturing in us (in me), the determination to, in the words of Zora Neale Hurston’s mother, ‘jump at de sun’.

As Hurston reflects, "we might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground." And that’s why black feminism matters, not just to me, but to all of us. It gives us the courage to try, the will to succeed and the reminder that as scholars, teachers and students that genius lies all around us (and not just in academic chambers).

In the context of our own commitment to civic engagement, as a University that aims to champion the voices of our community and privilege the narratives of those who are often marginalised, misunderstood and overlooked, as a community that shares the message that a University education is for anybody who wants it, black feminism’s message of democracy, inclusivity and understanding is crucial.

Walker reminds us that, “We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and if necessary, bone by bone” (‘Zora Neale Hurston: A Cautionary Tale and Partisan View’, p.92).

So the next time you are in the library, choosing an essay question, thinking about how you can use your English degree to make a difference in the world, remember Alice Walker, think about Patricia Hill Collins, think of Hurston’s mother’s words and make some theory come to life.

I’ll leave you with a brief reading list and a video made my one of our Arts Enterprise partners, Gemma Thorpe about a woman called Miss Punny. Gemma’s beautiful photos and sensitive film is the perfect complement to the books below and really captures the theme of creativity and life force that underpins Walker’s work.

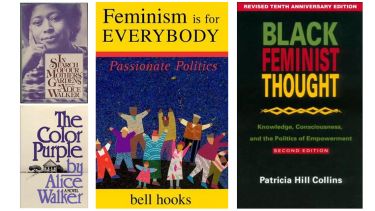

- Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (I’ve got The Women’s Press edition).

- Alice Walker, The Color Purple, (1982)

- Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought, (1990) – I have the revised edition.

- Bell hooks, Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, (2000).

See Gemma Thorpe’s Miss Punny documentary and photos.

Further reading and information sources

- UCU Report on BME women in academia

- The university professor is always white in The Guardian

- 14,000 British professors – but only 50 are black in The Guardian

- You can view all the videos in the #WeAreFeminists series on our YouTube playlist.

Written by Janine Bradbury, on 3 June 2013.